Let’s continue our alphabetic tour of common behavioral biases that distract otherwise rational investors from making best choices about their wealth. Today, we’ll tackle: familiarity bias, fear, framing, and greed, herd mentality, and hindsight.

FAMILIARITY BIAS

What is it? Familiarity bias is another mental shortcut we use to more quickly trust (or more slowly reject) an object that is familiar to us.

When is it helpful? Do you cheer for your home-town team? Speak more openly with friends than strangers? Favor a job applicant who (all else being equal) has been recommended by one of your best employees? Congratulations, you’re making good use of familiarity bias.

When is it harmful? Considerable evidence tells us that a broad, globally diversified approach best enables us to capture expected market returns while managing the risks involved. Yet studies like this one have shown investors often instead overweight their allocations to familiar vs. foreign investments. We instinctively assume familiar holdings are safer or better, even though, clearly, we can’t all be correct at once. We also tend to be more comfortable than we should be bulking up on our employer’s company stock.

FEAR

What is it? You know what fear is, but it may be less obvious how it works. As Jason Zweig describes in “Your Money & Your Brain,” if your brain perceives a threat, it spews chemicals like corticosterone that “flood your body with fear signals before you are consciously aware of being afraid.” Some suggest this isn’t really “fear,” since you don’t have time to think before you act. Call it what you will, this bias can heavily influence your next moves – for better or worse.

When is it helpful? Of course, there are times you probably should be afraid, with no time for studious reflection about an urgent life-saving act. If you are reading this, it strongly suggests you and your ancestors have made good use of these sorts of survival instincts many times over.

When is it harmful? Zweig and others have described how our brain reacts to a plummeting market in the same way it responds to a physical threat like a rattlesnake. While you may be well-served to leap before you look at a snake, doing the same with your investments can bite you. Also, our financial fears are often misplaced. We tend to overcompensate for more memorable risks (like a flash crash), while ignoring more subtle ones that can be just as harmful or much easier to prevent (like inflation, eroding your spending power over time).

FRAMING

What is it? In “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman defines the effects of framing as follows: “Different ways of presenting the same information often evoke different emotions.” For example, he explains how consumers tend to prefer cold cuts labeled “90% fat-free” over those labeled “10% fat.” By narrowly framing the information (fat-free = good, fat = bad; never mind the rest), we fail to consider the facts as a whole.

When is it helpful? Have you ever faced an enormous project or goal that left you feeling overwhelmed? Framing helps us take on seemingly insurmountable challenges by focusing on one step at a time until, over time, the job is done. In this context, it can be a helpful assistant.

When is it harmful? To achieve your personal financial goals, you’ve got to do more than score isolated victories in the market; you’ve got to “win the war.” As UCLA’s Shlomo Benartzi describes in a Wall Street Journal piece, this demands strategic planning and unified portfolio management, with individual holdings considered within the greater context. Investors who instead succumb to narrow framing often end up falling off-course and incurring unnecessary costs by chasing or fleeing isolated investments.

GREED

What is it? Like fear, greed requires no formal introduction. In investing, the term usually refers to our tendency to (greedily) chase hot stocks, sectors, or markets, hoping to score larger-than-life returns. In doing so, we ignore the oversized risks typically involved as well.

When is it helpful? In Oliver Stone’s Oscar-winning “Wall Street,” Gordon Gekko (based on the notorious real-life trader Ivan Boesky) makes a valid point … to a point: “[G]reed, for lack of a better word, is good. … Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge has marked the upward surge of mankind.” In other words, there are times when a little greed – call it ambition – can inspire greater achievements.

When is it harmful? In our cut-throat markets (where you’re up against the Boeskys of the world), greed and fear become a two-sided coin that you flip at your own peril. Heads or tails, both are accompanied by chemical responses to stimuli we’re unaware of and have no control over. Overindulging in either extreme leads to unnecessary trading at inopportune times.

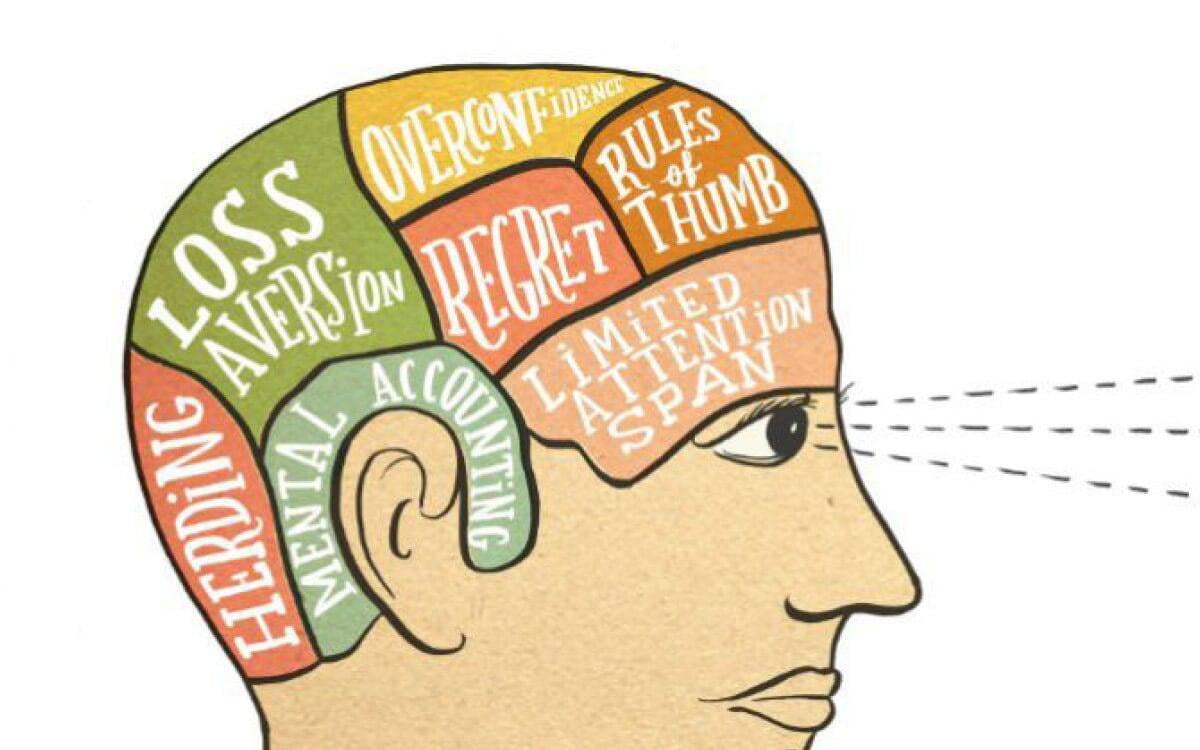

HERD MENTALITY

What is it? Mooove over, cows. You’ve got nothing on us humans, who instinctively recoil from or rush headlong into excitement when we see others doing the same. “[T]he idea that people conform to the behavior of others is among the most accepted principles of psychology,” say Gary Belsky and Thomas Gilovich in “Why Smart People Make Big Money Mistakes.”

When is it helpful? If you’ve ever gone to a hot new restaurant, followed a fashion trend, or binge-watched a hit series, you’ve been influenced by herd mentality. “Mostly such conformity is a good thing, and it’s one of the reasons that societies are able to function,” say Belsky and Gilovich. It helps us create order out of chaos in traffic, legal and governmental systems alike.

When is it harmful? Whenever a piece of the market is on a hot run or in a cold plunge, herd mentality intensifies our greedy or fearful chain reaction to the random events that generated the excitement to begin with. Once the dust settles, those who have reacted to the near-term noise are usually the ones who end up overpaying for the “privilege” of chasing or fleeing temporary trends instead of staying the course toward their long-term goals. As Berkshire Hathaway Chairman and CEO Warren Buffett has famously said, “Investors should remember that excitement and expenses are their enemies. And if they insist on trying to time their participation in equities, they should try to be fearful when others are greedy and greedy only when others are fearful.” Well said, Mr. Buffett!

HINDSIGHT

What is it? In “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman credits Baruch Fischhoff for demonstrating hindsight bias – the “I knew it all along” effect – when he was still a student. Kahneman describes hindsight bias as a “robust cognitive illusion” that causes us to believe our memory is correct when it is not. For example, say you expected a candidate to lose, but she ended up winning. When asked afterward how strongly you predicted the actual outcome, you’re likely to recall giving it higher odds than you originally did. This seems like something straight out of a science fiction novel, but it really does happen!

When is it helpful? Similar to blind spot bias (one of the first biases that was covered), hindsight bias helps us assume a more comforting, upbeat outlook in life. As “Why Smart People Make Big Money Mistakes” authors Gary Belsky and Thomas Gilovich describe it, “We humans have developed sneaky habits to look back on ourselves in pride.” Sometimes, this causes no harm, and may even help us move past prior setbacks.

When is it harmful? Hindsight bias is hazardous to investors, since your best financial decisions come from realistic assessments of market risks and rewards. As Kahneman explains, hindsight bias “leads observers to assess the quality of a decision not by whether the process was sound but by whether its outcome was good or bad.” If a high-risk investment happens to outperform, but you conveniently forget how risky it truly was, you may load up on too much of it and not be so lucky moving forward. On the flip side, you may too quickly abandon an underperforming holding, deceiving yourself into dismissing it as a bad bet to begin with.

There aren’t any for letters I, J, or K, but there's more behavioral biases to cover in upcoming installments, so stay tuned.

In the meantime, feel free to...

This content is developed from sources believed to be providing accurate information. The information in this material is not intended as investment, tax, or legal advice. It may not be used for the purpose of avoiding any federal tax penalties. Please consult legal or tax professionals for specific information regarding your individual situation. The opinions expressed and material provided are for general information, and should not be considered a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security. Digital assets and cryptocurrencies are highly volatile and could present an increased risk to an investors portfolio. The future of digital assets and cryptocurrencies is uncertain and highly speculative and should be considered only by investors willing and able to take on the risk and potentially endure substantial loss. Nothing in this content is to be considered advice to purchase or invest in digital assets or cryptocurrencies.

Enjoying Escient Financial’s Insights?

The weekly newsletter is usually delivered to your email inbox Friday or Saturday, and includes:

- the latest Escient Financial Insights articles

- a brief of the week's important news regarding the markets

- recommended third-party reads

- selected Picture of the Week

Escient Financial does NOT sell subscriber information. Your name, email address, and phone number will be kept private.